“Feeling the Future” of Bem’s Findings

July 13, 2015 by tanclabadmin2 CommentsEdit

Here we have a guest blog from Michael Duggan who is one of the authors of the meta-analysis of replications of Daryl Bem’s controversial retroactive facilitation experiments http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2423692, and has a long term interest in serious psi research. He is classically trained in the sciences (Ph.D Catalytic chemistry), but it is psi research that truly excites him. Here, he blogs about the controversy surrounding the publication of Daryl Bem’s seminal Feeling The Future Paper in 2011, and the experience of trying to publish a meta analysis of 90 experiments supporting Bem’s earlier findings.

“Feeling the Future” of Bem’s findings

The publication of the paper “Feeling the future: experimental evidence for anomalous retroactive influences on cognition and affect” in the mainstream and highly esteemed Journal of Personality and Social Psychology in 2011 by Daryl Bem (Bem, 2011), professor emeritus at Cornell University, was the academic equivalent of a Big Bang for many scientists and lay persons alike because the heretical message was “precognition is scientifically supported”.

But what did Daryl Bem find really? In a series of nine experiments, he found that in four different tasks, the performance of the participants was related to what happened after their decision was made. For example, he found that participants were able to detect behind which door hid an erotic image approximately 3% above chance level or avoid a negative image nearly 2% above the expected chance level. In another task, defined as retroactive facilitation of recall, participants recalled approximately 2 to 4% more words if they were later repeated several times. In another study, subjects were exposed to a prime after categorizing a picture as pleasant or unpleasant. Bem showed that when the future prime was congruent, i.e., pleasant prime – pleasant picture, the reaction times were faster. It is as if the future can percolate into the present to influence participant’s behavioural responses in these standard but time-reversed psychological tests.

To have an idea of the impact of this paper, it is instructive to take note of the number of times this paper was cited in other scientific journals: 342 times as of 03th July 2015. Furthermore if you search “Feeling the future” with Google you can find approximately two million pages that includes a dedicated page on Wikipedia. Additionally Bem was interviewed by many radio and TV stations, from the Colbert Report to the David Letterman show and Through The Wormhole with Morgan Freeman. Such widespread and generally positive media coverage is unprecendented for any kind of parapsychological type finding. Bem deserves plaudits for breaking new ground in this way.

It is also extremely important to bear in mind that evidence for precognition is not limited to the behavioural studies of Bem and others but extends to presentiment effects in human physiology (Mossbridge, et al, 2012) and forced choice guessing (Honorton and Ferrari, 1989).

This event is quite interesting to observe both from the scientific and sociological point of view. From a scientific point of view, it is curious to note that most other papers related to “parapsychological” stuff published in mainstream journals (e.g. Psychological Bulletin, British Journal of Psychology) did not receive similar “attention” even if they usually referred to telepathy or distant mental interaction. Very probably, precognition is deemed not so “woo” as other parapsychological phenomena. This more favourable attitude to precognition might have something to do with recent serious attention to the idea of retrocausation in quantum mechanics through the work of physicists such as John Cramer and Daniel Sheehan. Indeed, several AAAS (The American Association for the Advancement of Science) symposia have been dedicated to exploring retrocausality from both a physics and parapsychological perspective, inviting contributors from both fields.

As expected, Bem’s paper was analyzed and criticized, in particular by scientists, starting from theoretical grounds progressing into qualms about methodology and statistics, and finally questioning Bem’s interpretation of results. The main theoretical criticisms stand on the premise that “precognition” does not exist and hence all evidence supporting it is surely based on flawed procedures or interpretations. It is clear that this attitude is based on a prejudiced old Newtonian ideology rather than an examination of the state of the debate. As mentioned above, serious scientists are exploring retrocausation with obvious implications for the possibility of precognition. More generally, quantum mechanics with its basis in probability theory, non-locality, and entanglement effects is so strange and counter-intuitive, that outlawing parapsychological phenomena because they contradict the so-called laws-of-physics seems somewhat premature. More interesting, are the criticisms related to methodology and statistics. Initially criticisms of the reviewers and the editor that accepted the paper for publication evolved into an attack on the type of statistics used, a situation inflamed by the fact that 8 out of 9 experiments yielded statistically significant results that were “too good to be true”. Eventually these discussions lead to a more general critique –in some quarters – of how ALL psychology experiments are conducted leading to constructive advice moving forward, for example; specifying a priori which hypotheses are exploratory and which ones are confirmatory, pre-registering the studies in order to reduce so-called questionable research practices (i.e. optional stopping in the data collection; post-hoc selection of only statistically significant comparisons; arbitrary elimination of outliers, etc.), and ultimately including the abandonment of frequentist statistics in favour of Bayesian ones. This last criticism is particularly interesting because the debate, supported by scientific papers, yielded very different results using the same data. For example, Eric-Jan Wagenmakers of the Department of Psychology University of Amsterdam and his colleagues (Wagenmakers, et al.,2011), found weak to nonexistent support when analyzing Bem’s data, whereas a rebuttal by Bem, with two experts in Bayesian statistics (Bem et al., 2011), found strong support. Another independent Bayesian analysis carried out by Jeff Rouder of the Department of Psychological Sciences University of Missouri and Richard Morey of the Rijksuniversiteit in Groningen(Rouder and Morey, 2011), concluded as follows:“There is some evidence, however, for the hypothesis that people can feel the future with emotionally valenced nonerotic stimuli, with a Bayes factor of about 40. Although this value is certainly noteworthy, we believe it is orders of magnitude lower than what is required to overcome appropriate skepticism of ESP”. A Bayes factor of 40 in this case means that Bems’ data are 40 times more likely to have occurred under the hypothesis that “feeling the future” is true than under the hypothesis that it is not true. It is curious to note that for the supporters of the Bayesian approach, a Bayes factor of 30 is considered as strong support to the hypothesis.

This continued enhancement of the criteria of scientific evidence to accept parapsychological phenomena, is quite interesting. For example, as for all other lines of research, a given phenomenon is considered more probable if it is observed by independent replications. In a recent meta-analysis of all experiment related to “feeling the future”, we found 90 studies overall, conducted by Bem and thirty others, that elicited very strong support all of Bem’s original experiments with the exception of the retroactive recall facilitation tasks. However, yet again, this evidence was deemed insufficient by skeptics, in particular by Wagenmakers (Wagenmakers, 2014), in part because most of these experiments were not pre-registered and hence it cannot be excluded that the experiments are contaminated by flawed procedures and statistical analyses. Also, recently, Daniel Lakens has provided a critique based on our assumptions of the file drawer: http://daniellakens.blogspot.nl/2015/04/why-meta-analysis-of-90-precognition.html. We are in the process of providing a robust argument to his conclusions, but it is worth noting that if we were to apply such a stringent approach to existing meta-analyses related to psychological investigations, most would be viewed as suspect.

Final reflections: Though we do not believe there is a file-drawer problem, we are in the process of setting up collaborative pre-registered replications so this criticism will not apply to future experiments.

References

Bem, D. J. (2011). Feeling the future: experimental evidence for anomalous retroactive influences on cognition and affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 100(3), 407-425.

Bem, D., Utts, J., Johnson, W.O. (2011). Must psychologists change the way they analyze their data?Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101(4), 716-719.

Honorton, C., and Ferrari., D. (1989) “Future Telling” A meta-analysis of forced choice precognition experiments, 1935 – 1987.

Journal of Parapsychology, Vol. 53. December 1989.

Mossbridge, J., Tressoldi, P., and Utts, J. (2012) Predictive physiological anticipation preceding seemingly unpredictable stimuli: a meta-analysis.

Frontiers in psychology. 17th October 2012.

Rouder, J. N., & Morey, R. D. (2011). A Bayes factor meta-analysis of Bem’s ESP claim. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 18(4), 682-689.

Wagenmakers, E. J., Wetzels, R., Borsboom, D., & van der Maas, H.(2011). Why psychologists must change the way they analyze their data:The case of psi: Comment on Bem (2011). Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 100, 426–432.

Wagenmakers, E.J. (2014). http://osc.centerforopenscience.org/2014/06/25/a-skeptics-review/

Unconsciously bringing down the house

March 24, 2015 by tanclabadmin1 CommentEdit

Isn’t the fact that casinos thrive, strong evidence against precognition? This is one of the most frequent questions/comments we hear with regards to our work, so we wanted to use this blog post to answer the question.

The fact that casinos do in fact maintain their edge, does suggest that people cannot consciously, or willfully, gain access to precognitive information in a terribly reliable manner. However, it does not rule out the existence of precognition that manifests more intuitively, or unconsciously. Psychologists have shown that information can exist in our minds that we are not consciously aware of, information that, for whatever reason, does not translate into conscious awareness; yet there are methods psychologists can use to access this information which is hidden from conscious awareness.

Some of the earliest work on this topic was most famously conducted with patient HM, who underwent brain surgery that removed part of the temporal lobe, the hippocampus. After initial post-surgery assessment, doctors saw that HM could carry on coherent conversations and was in fact quite lucid. Yet on further inspection it became very clear that there was something wrong with his memory. He had lost his ability to translate short term memories into long-term memory. For example, after meeting a new person (post-accident) if that person would leave the room and come back, they would have to be re-introduced. Psychologists initially thought that this meant that all new learning would be compromised. Yet researchers found out that certain types of learning and memory remained intact – specifically unconscious, or implicit learning. For example, after many sessions of learning a task like mirror drawing, even though his skills would improve on the task, he would have no awareness of ever doing the task before. Each time he did the task, it would seem to him like it was his first time. This type of amnesia, in which new explicit learning is compromised, is termed anterograde amnesia. The main character in the movie ‘Memento’ is a great example of someone with anterograde amnesia.

This groundbreaking work not only spawned modern cognitive neuropsychology but helped demonstrate very clearly an important fact about the human mind; the things that we are consciously aware of are only a very small part of the information available that influences our decisions and actions. Perhaps what is most problematic with this is that we tend to treat our conscious perceptions as the whole story, when in fact a bulk of the action takes place outside of our awareness.

When it comes to precognitive information, it is possible that we all might be akin to patient HM (i.e., perhaps suffering from a type of ‘retrocausal amnesia’ – unable to explicitly access this future information). For example, you could tell HM the following day’s winning lottery numbers, but despite this information, as soon as he’s distracted for long enough, the information would be lost to conscious memory. Perhaps we similarly are unable to access unconscious precognitive information. Importantly, psychologists have come up with clever ways to demonstrate the existence of these memory traces even when they cannot be explicitly communicated (e.g., using indirect behavioral and physiological methods).

This is the type of methodology we will be using in our experiments at the TANC lab. For example, instead of asking our participants to tell us what they think is going to happen in the future, we will measure their brain waves and/or reaction times to stimuli and see if it can reveal information about future events. In 2012, Mossbridge and colleagues analyzed all studies from 1978-2010, showing that there is in fact evidence across all studies of physiological pre-arousal that corresponds to randomly chosen future stimuli.

Therefore, the fact that casinos still thrive is not strong evidence against the existence of precognition. Given how compelling it would be to be able to “beat the house” or consistently predict stock market outcomes, our experiments are aimed at using unconscious precognition to predict these types of real-world outcomes. In future blog posts we’ll describe in more detail the TANC experiments- one of which is specifically targeted at using unconscious precognition to win at roulette!

Stay tuned!

Introducing Dr. Stephen Baumgart

January 23, 2015 by tanclabadminLeave a commentEdit

Dr. Stephen Baumgart

President

Greetings! I am the founder and president of the TANC Lab. My interest in science dates back to elementary school when I would spend recess in the library, vociferously reading all the books on space travel. Carl Sagan’s TV series and book “Cosmos” inspired me to choose science as a career while in middle school.

I realized I’d need to study hard to achieve this dream; therefore, I slowly improved my math and science ability from below average in middle school, to being one of the top students by the time I entered U.C. Davis as a physics major. It was at U.C. Davis that I was introduced to the possibility of retrocausality. We were taught that no laws of physics prohibited backwards-in-time communication but that there was no experimental evidence for it (which I later found out that this is not strictly true because of precognition research!). Upon graduation from U.C. Davis, I continued studying physics as a graduate student at Yale University, receiving my Ph.D. in 2009.

I’ve always had a broad interest in science, paying attention to cutting-edge research across multiple fields. At Yale, I became interested in the mystery of consciousness and the various debates regarding how subjective experience can arise from brain activity, but no explanation seemed satisfactory to me. It still seems impossible to figure out how to explain subjective experience in terms of current science. I was also interested in neuroscience research which seems to show that conscious awareness of intention lags behind the decision processes that lead to behavior (e.g., the work of Benjamin Libet). The presentiment research we’re working on now will certainly have important implications regarding our notion of “free will”. By developing solid paradigms to study precognition we will be able to make headway on what have seemed largely intractable problems in the philosophy of science.

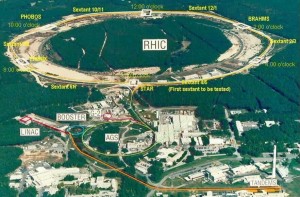

Meanwhile, I spent most of my time at Yale enduring hard classes like Quantum Field Theory and then doing my dissertation research on high-energy nuclear physics. I worked in the STAR at RHIC collaboration (the acronym stands for “Solenoidal Tracker At the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider). The RHIC collider would smash gold ions, copper ions, deuterons, or protons together at near the speed of light in order to study the nuclear forces which bind quarks and gluons within nucleons and nucleons within nuclei.

The Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider:

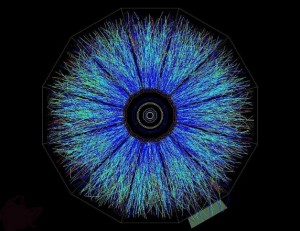

My dissertation research focused on the production of charm quarks in copper on copper collisions. A picture of the STAR detector readout is below:

As it turned out, Professor John Cramer, the developer of the Transactional Interpretation of quantum mechanics, was also a member of the STAR collaboration. A key aspect of Transactional Interpretation is that quantum interactions are explained in terms of advanced (backwards-in-time) and retarded (forwards-in-time) waves. I also learned about Prof. Cramer’s work investigating retrocausal communication using quantum optics. He believed it might be possible to communicate backwards in time based on standard quantum mechanics. However, he has found a flaw in his calculations invalidating his current experimental design.

After graduating from Yale, I continued my work in high-energy nuclear physics at the RIKEN Radiation Laboratory in Wako, Japan (just outside Tokyo). I worked in the PHENIX experiment (Pioneering High-Energy Nuclear Interaction eXperiment) on a RIKEN postdoctoral fellowship for three years. I was in Japan during the devastating earthquake, tsunami, and nuclear meltdown in Fukushima. My supervisor went to Fukushima prefecture to do radiation monitoring while I continued data analysis in Wako.

At RIKEN I continued being interested in retrocausality, stumblingly upon Prof. Dick Bierman’s work in unconscious precognition. Reading other papers in the field, the results appeared to be solid and good evidence of retrocausality. This research is important to our understanding of physics, neuroscience, and psychology so precognition research should be prioritized to understand the underlying causes behind this phenomenon.

After my RIKEN fellowship expired, I initially desired to continue an academic career. However, the so-called “two-body problem” would make it extremely risky and difficult to start a family while following a traditional academic career. So instead of being depressed that so few scientists were investigating presentiment and retrocausality, I decided to try it myself! I ran my own informal project copying an experimental design from Dean Radin, but it became apparent that I would need more resources and colleagues in order to do professional-quality work; therefore, I founded the TANC lab. I plan for our lab to undertake pioneering high-quality research into the nature of time and consciousness. Be sure to sign up for our email list and we will keep you posted on all our exciting new discoveries!

Introducing Dr. Michael S. Franklin

January 14, 2015 by tanclabadmin5 CommentsEdit

Introducing Dr. Michael S. Franklin

Treasurer/Director of Research and Development

I’m thrilled to have this incredible opportunity to be the Director of Research and Development at the TANC lab. Although on one hand, this seems to be the culmination of many years of work on topics related to the brain, consciousness, and cognition (which I will describe below), on the other hand, I’ve been well aware that forming such a lab to investigate controversial aspects of time would be a long-shot. After all, funding for such work is especially difficult to obtain, and my advisors and mentors throughout the years have made it clear how risky such research endeavors are career-wise. Despite these risks, it has been curiosity that has driven me to keep pursuing this work. In this post, I want to give a brief overview of where this curiosity has led me over the past 20 years!

The questions that most interest me are the big ones – for example, how do our minds work? How do minds arise from something physical, like the brain? What are the mind’s capacities? What can learning more about the mind reveal about the nature of the universe and reality in general? As an undergraduate at University of Wisconsin, I decided majoring in psychology and zoology would give me the best foundation to get at these questions. At University of Wisconsin I had some great research experiences, first at the Primate Center, followed by volunteering in a sleep lab at the Psychiatry Department in the Medical School. At the time my main interest within psychology was dreams, lucid dreaming in particular, so it was exciting to get hands-on experience in a sleep lab.

Gearing up for graduation and unsure of my future plans, although tempting as it was to pursue my rock band dreams…

on a whim I sent a note to Stephen LaBerge, who literally wrote the book on lucid dreams, inquiring about an opportunity to work in his lab at Stanford University.

Well, as luck would have it, he invited me out to his lab where I spent about a year studying lucid dreaming – the ability to become aware within the dream that you are dreaming. This was an exciting time, working evenings in the sleep lab with subjects who could reliably have lucid dreams in the laboratory and indicate this with trained eye-movements (the “lucidity signal”). To be able to watch the subjects’ brain waves and eye-movements in real-time from a separate room, and know they are in REM sleep and dreaming, yet see them indicating pre-communicated signals with their eyes was fascinating. It really felt like pioneering work – using the scientific method to explore the bounds of consciousness.

At this same time I was first exposed to experimental parapsychology as a research assistant on a project measuring EEG during a telepathy experiment (a Ganzfeld procedure). After witnessing some intriguing sessions I became more open to the possibility that the current mainstream scientific worldview, which excludes phenomena like telepathy and precognition, may not be the final word on such matters. At this time I began to settle on cognitive neuroscience as a path for trying to understand important questions about consciousness. After all the common phrase of the day was, “the mind is what the brain does”, so why not study the brain to learn more about the mind.

So after spending a year at Stanford, I pursued a master’s degree in psychology at Tulane University, gaining experience in EEG by doing studies on language processing. Then I went to University of Michigan for my doctoral degree, receiving a PhD in cognitive psychology, studying a range of topics on language, memory, and attention. My dissertation project involved work with fMRI, investigating how the brain processes order information. I also had the opportunity to work with trained musicians (this time as a researcher), examining the cognitive benefits of early and extended training in music.

While pursuing this post-graduate work I still maintained an interest in more ‘fringe’ topics, and had an amazing opportunity to do a summer research internship at the Princeton Engineering Anomalies Research Laboratory (PEAR lab) investigating mind-matter interactions. Also, somewhat to my surprise, I had an opportunity to be a teaching assistant for a course at University of Michigan; Psychology of Consciousness. However, this wasn’t a typical college course on consciousness that focused on brain and behavior. Instead, we discussed topics like remote viewing, precognition, and lucid dreaming and read about consciousness from different perspectives (e.g., Ken Wilber – “No Boundary”). At this time I was in touch with Daryl Bem and Dean Radin regarding their work on precognition and realized what little work had actually been done investigating implicit or unconscious precognition using basic cognitive psychology paradigms and methodology that I had been learning about in graduate school (measuring variables like reaction time and error rates). Towards the end of my time at U of M, I began developing and testing out my own basic precognition paradigms. Although this work was understandably treated with skepticism, I was lucky to have found mentors that allowed me the freedom to explore this work; and perhaps much to their surprise, I was finding results that seemed to support the hypothesis of precognition.

As timing would have it, just as I was graduating from U of M in 2008, Dr. Jonathan Schooler was about to move to the University of California, Santa Barbara, and with a 3-year grant to study precognition and other forms ‘anamolous cognition’, he was looking for a post-doc and I was looking for a job. Now it’s been over six years that I have had the privilege of working with Dr. Schooler in the META lab, first as a post-doc and now a project scientist at UCSB in the Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences. At UCSB, I’ve found a great research environment where I’ve been able to continue work on precognition with his support and guidance, and also work on topics related to consciousness and cognition that actually turn out to be quite relevant to the work on precognition; specifically, the role of attention, or more specifically the lack of attention (i.e., mind-wandering) and meta-awareness on task performance. Now with over thirty publications in mainstream journals, and serving as a reviewer for articles, I have a great deal of experience developing and critiquing experimental designs and statistical analyses. I think this in particular has allowed me to create tight experimental protocols and given me a keen eye for difficult to detect confounds which is critical in this kind of work.

So it was extremely exciting to get connected with Dr. Stephen Baumgart this past year, who not only has a similar vision for approaching this work on precognition in an unbiased and rigorous way, but was also willing to put in the seed money for the lab out of his own pocket while we seek outside funding to keep the lab sustainable. As mentioned in our earlier post, headway on this difficult topic will take a concerted effort, and with the TANC lab, we hope to have the opportunity to do just that. By building on the work we have already done, I think we are in a great position to make some real progress on this important topic which has such profound implications.

In future blog posts, I’ll be discussing this earlier work in more detail and my own views on the current controversy in the field. Stay tuned!

Welcome to the TANC Lab’s First Blog Entry

January 5, 2015 by tanclabadmin4 CommentsEdit